The Mind is a collaborative card game that is designed to be fun to play with your friends. I had fun playing it with my friends a couple of weekends ago. The basic rules of the game are pretty simple:1

- There are 100 cards in the deck, numbered 1 to 100.

- In round \( R \) each player is dealt \( R \) cards.

- The object of the game is to play2 the cards in order, such that a player never plays a card when a lower card exists in another player’s hand.

- The players are not allowed to communicate in any way, aside from maybe making the odd facial expression.

- If all the cards are played in the correct order then the players win that round and move onto the next round.

The game is fun because you need to try and work out how hesitant or confident each other player is and learn how long it is likely to take them to put a certain card down. Slowly, the group gets better at doing this and there is a nice sense of progression. Assuming everyone can count reliably (a big assumption), there is one strategy that “solves” the game: each player waits \( X \) seconds before playing their lowest card, where \( X \) is the difference between the value on their lowest card, and the current visible card. I think playing this way is a bit boring and against the spirit, however.

One question caught in my mind when I was playing: what is the probability, given my cards and the current state of the game, that I have the lowest card of all players, and therefore should play next? In the rest of this post, in order to polish up my fast-rusting probability skills, I’m going to try to work that out.

For the sake of generality, let’s say the deck has size \( L \) (\( L=100 \) for the standard game). The current face-up card is \( F \), and the value of the lowest card in my hand is \( C \). Let \( M_0 \) denote the number of cards I hold, and \( M_i \) the number of cards that player \( i \) holds. We can condense the state of the game into three key quantities:

- The number of remaining cards lower than my lowest: \( n_l = C - F - 1 \)

- The total number of other remaining cards aside from my own: \( n_r = L - F - M_0 \)

- The number of cards other players hold: \( n_c = \sum^N_{i=1}M_i \)

To give a concrete example, consider the following case, where \( L=12 \), and the current face-up card is 3, so \( F=3 \). Let’s say there are 2 other players, each with 2 cards (\( n_c=4 \)). In this example we are holding 7 and 9. I have illustrated this on the handy number line below.

$$ \color{red}{1\quad2 \quad 3} \color{black} \quad 4 \quad 5 \quad 6 \color{green} \quad 7 \color{black} \quad 8 \color{green} \quad 9 \color{black} \quad 10 \quad 11 \quad 12 $$We have that \( n_l = 3 \) (cards 4, 5, 6 are lower than our 7), and \( n_r = 7 \) (the remaining unknown cards are 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11 and 12). The easiest way3 to solve this is using a combinatorial approach. We want to work out the total number of different ways the cards could have been dealt to the two other players, and then find the number of ways, of these, in which we have a lower card than them.

The total number of possible deals is given by \( \binom{n_r}{n_c} \), the number of ways we can choose the \( n_c \) cards held by others from the set of \( n_r \) remaining unknown cards.4

To find the number of winning scenarios (where we have the lowest card), we must count the deals where none of the other players hold a card from the “lower” set (\( n_l \)). This implies that all \( n_c \) cards held by the other players must be chosen strictly from the cards higher than ours. The number of such high cards available is \( n_r - n_l \). Therefore, the number of winning deals is \( \binom{n_r - n_l}{n_c} \).5

Dividing the winning deals by the total deals gives us the probability:

$$ P(\text{I am lowest}) = \frac{\binom{n_r - n_l}{n_c}}{\binom{n_r}{n_c}} $$Using our example numbers (\( L=12 \)):

$$ P = \frac{\binom{7 - 3}{4}}{\binom{7}{4}} = \frac{\binom{4}{4}}{35} = \frac{1}{35} \approx 2.9\% $$In this case, there are exactly 4 cards higher than our 7 available (8, 10, 11, 12). Since the other players need exactly 4 cards, there is only 1 specific deal where they don’t have a low card. Any other combination would force them to hold at least one card lower than ours.5

Ok, I have a formula to work out the probability I should play next (i.e. I have the lowest card), can we glean some sort of helpful insight from this?

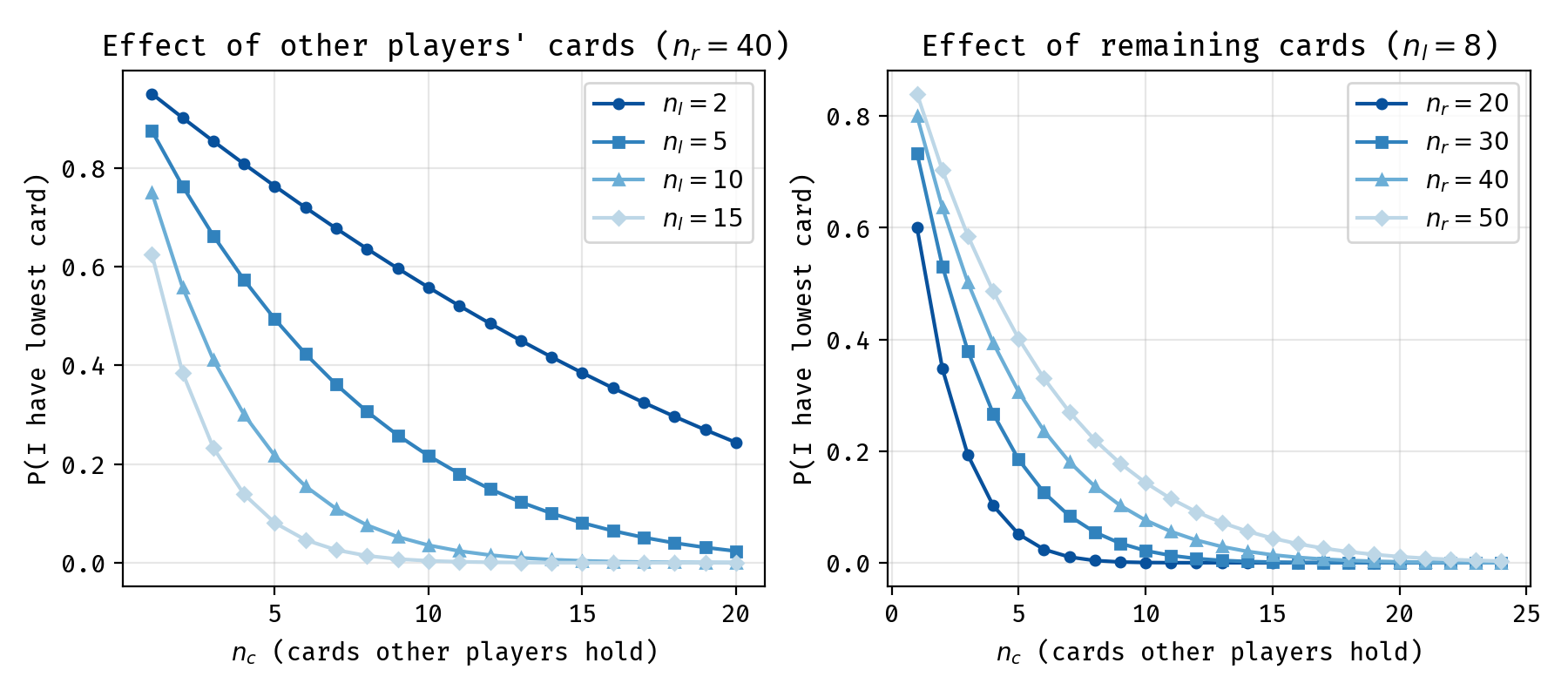

Probability of having the lowest card as a function of various game parameters.

Here are some nice looking plots. One thing is immediately obvious on both of these plots (and probably would have been without any analysis): the more cards other players hold, the lower the probability that you should play next. What is perhaps slightly less obvious is how this interacts with the other variables. We can see that as the difference between your lowest and the face up card grows, the influence of the number of cards other players hold becomes stronger. As the number of remaining cards grows (i.e. earlier on in the round), the probability you should play next becomes larger. Feel free to take your own insights from the plots, or just enjoy the tasteful shades of blue.

Generally, people aren’t very good at computing binomial coefficients in their head. This means that the analysis we have done so far is perhaps of limited utility in the tense, in-game environment. Fortunately, we can substitute the combinatorics for a simple heuristic. First, estimate the fraction of the unknown cards that are currently held by your opponents (\( n_c/n_r \)). Then, treat every number in the gap between the face-up card and your hand as an independent risk. The probability you are the lowest is roughly

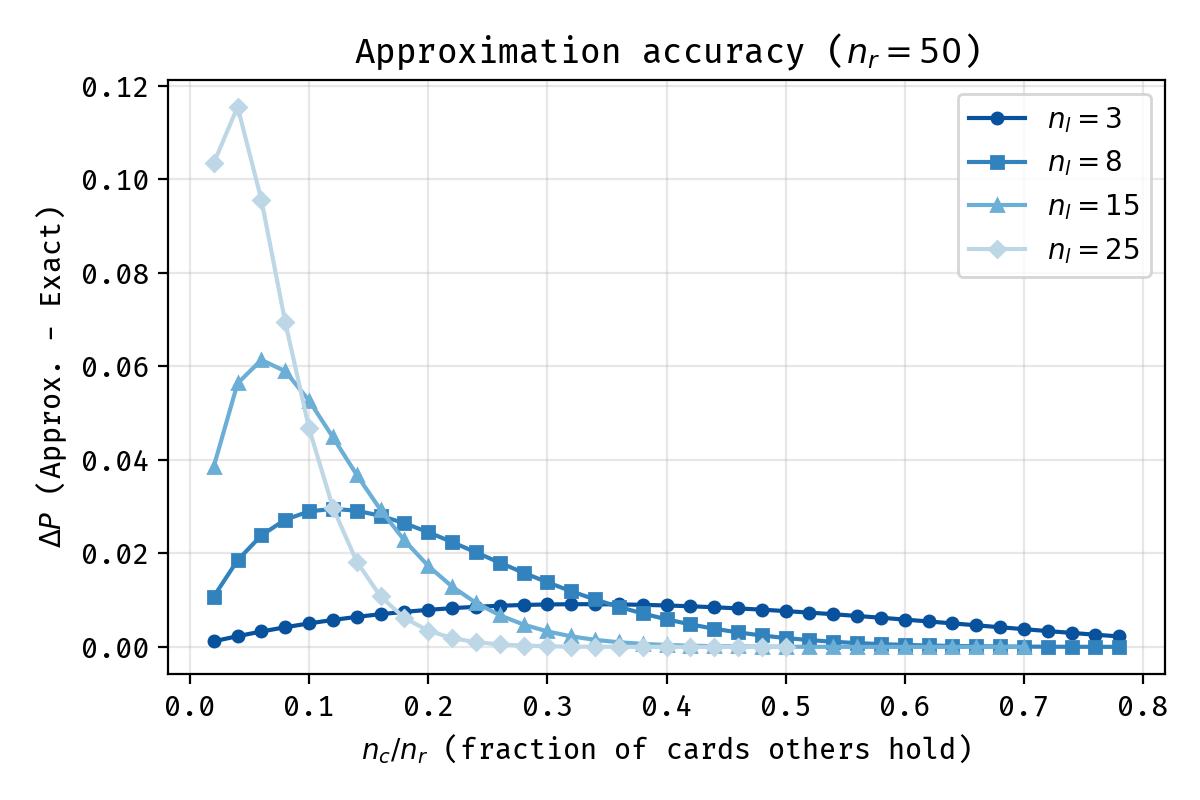

$$P(\text{I am lowest}) \approx(1 - \frac{n_c}{n_r})^{n_l}.$$For example, if the other players hold half the remaining deck, surviving a gap of 2 cards is like winning two coin flips in a row (\( 0.5^2 = 25\% \)). Because this approximation assumes independent events (sampling with replacement), it yields an optimistic upper bound. This difference arises because the real game involves sampling without replacement: successfully “surviving” one number shrinks the pool of safe cards, making it progressively more likely that an opponent holds the next number in the sequence. This is maybe feasible to do in your head if you are quite smart/fast. The plot below shows the error of this approximation. Basically, it’s less accurate when the number of lower cards is higher, and the fraction of cards others hold is small (unless this fraction is really small).

Error of the approximation method.

-

There are some extra gimmicks like extra lives and power-ups, but let’s forget them for now. ↩︎

-

To play a card, remove it from your hand and place it face up on the table. ↩︎

-

i.e. the only way I can currently think of. ↩︎

-

Here \( \binom{n}{k} \) is the binomial coefficient. ↩︎

-

It is worth noting the boundary condition here. By definition, the binomial coefficient \( \binom{n}{k} \) is zero if \( k > n \). In our game, this happens if the number of cards the opponents hold (\( n_c \)) is greater than the number of “safe” high cards available (\( n_r - n_l \)). This implies the probability is exactly 0. ↩︎ ↩︎